| 关联规则 | 关联知识 | 关联工具 | 关联文档 | 关联抓包 |

| 参考1(官网) | |

| 参考2 | |

| 参考3 |

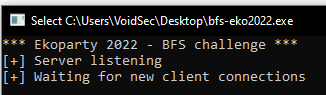

Last month, during Ekoparty, Blue Frost Security published a Windows challenge. Since having a Windows exploitation challenge, is one of a kind in CTFs, and since I’ve found the challenge interesting and very clever, I’ve decided to post about my reverse engineering and exploitation methodology.

Challenge Requests

- Only Python solutions without external libraries will be accepted

- The goal is to execute the Windows Calculator (calc.exe)

- The solution should work on Windows 10 or Windows 11

- Process continuation is desirable (not mandatory)

You can download the target application here (backup).

High-Level Analysis

When exploring an unknown executable, one of the first things I always check is the security features that were built into the binary when it was compiled. If on Linux I’m used to checksec.sh, on Windows I use winchecksec or PESecurity; they aren’t kept updated but they serve our purpose.

Doing so, resulted in the following mitigations:

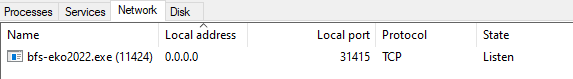

Some of these details can also be confirmed, at runtime, with a tool like System Informer (former Process Hacker):

![]()

This means that we are dealing with an x64, un-obfuscated, C++ (checked with DIE) compiled binary with ASLR, DEP and stack-canaries enabled mitigations but no CFG.

Once executed, the binary binds on 0.0.0.0, port 31415, and awaits client connection.

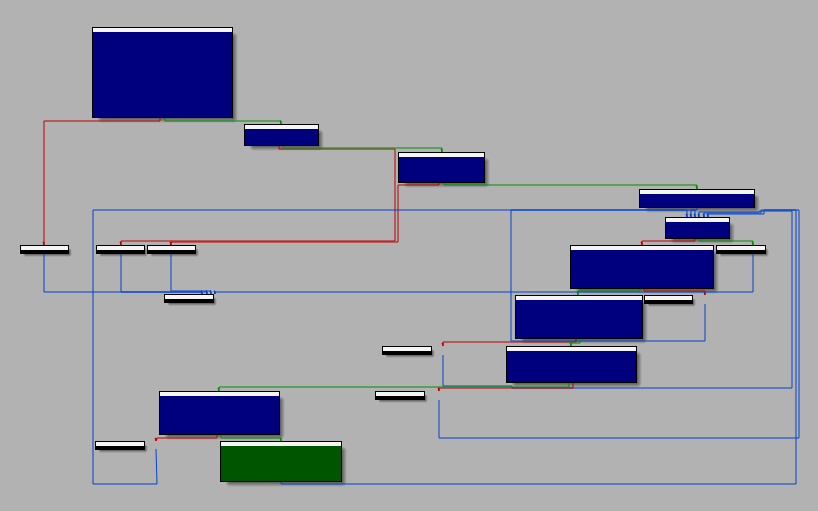

As per my methodology, I’ve proceeded with reverse engineering the high-level functionalities of each code block, renaming them with some meaningful labels. One thing that also helps me better visualize the code flow is colouring blocks:

- Blue shades: nodes that I’m stepping through while debugging or paths followed by the software. For more complex software I’m generally tracing the execution flow with tools like PIN, Dynamorio and the Tenet IDA’s plugin.

- Green shades: blocks that I want to reach or that are holding main/interesting functionalities I’d like to explore.

- Black/grey: error messages/irrelevant code sections.

- Orange: possible logic vulnerabilities that I’d like to further examine.

- Red: possible memory corruption vulnerabilities that I’d like to further examine.

I’ve then collapsed all irrelevant nodes, leaving me with the following simplified code graph:

Handshake

I usually combine debugging and static code analysis in order to get the most out of both. I then proceeded to write a simple python “client” to interact with the target.

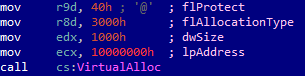

As soon as the software start, an always static (both in size and memory address) buffer is allocated in the heap:

As we can see from the VirtualAlloc() API call above, the buffer is allocated at address 0x10000000 and it is of size 0x1000 (4096 bytes); the memory protection for the region is RWX.

After that, we find the socket initialization, the server binding, and then it enters a loop, waiting for a client connection.[出自:jiwo.org]

Note: the server is not multithread and only one client per time is allowed.

Data sent to the server is stored in the previously allocated heap-buffer and then a function is called. This function, opportunely renamed as handhshake_check(), has the following prototype: handhshake_check(uint buffer_length, *buffer) and once decompiled it results in the following code:

This function verifies if the first 6 characters of our buffer match with the string “Hello“; if it does, the execution continues and the software sends back “Hi“.

Data Processing

After that, the execution flow is transferred to another function, which I’ve renamed as data_processing() and decompiled as follows:

In this function:

-

Previously allocated heap-buffer is filled with 0x5050505050505050 and 0xCF58585858585858.

Note: this is weird as memory is usually initialized to 0. - Another packet is expected; this time the content is saved on a stack buffer.

- If the received packet is at least 11 bytes then the function checks if the packet contains a specific “cookie value” 0x323230326F6B45 (“Eko2022“).

- Then the first byte after the “cookie value” is checked for the presence of the T character. This field is used to determine the packet’s type.

- Then the 2 bytes after the packet’s type are treated as the size of the packet’s data. The packet data’s size must be lower than 0xF00 (3840 bytes).

I’ve named this structure: packet_header

After our packet’s header passes all the above validations, the server wait for the packet’s data. This packet (packet_data) will be saved in the previously allocated heap-buffer.

char_replace()

Then a function renamed as char_replace() is called; this function copies the content of packet_data (stored in the heap), to a stack buffer (CmdLine) of size 0xF00 (3840 bytes). While copying the data, it replaces all the occurrences of bytes 0x2B and 0x33 with null-bytes.

After the copy and character replacement, the resulting data is sent back to the client.

Chaining Vulnerabilities

Integer Overflow

The packet_data_len comparison (which IDA’s decompiler fails to visualize adequately) is odd enough to investigate. As we can see from the raw assembly:

The packet_data_len value is loaded into the EAX register by the MOVSX opcode.

MOVSX: copies the contents of the source operand to the destination operand and sign extend the value. In 64-bit mode, the instruction’s default operation size is 32 bits.

JLE: It is a conditional jump that follows a test. It performs a signed comparison jump after a cmp if the destination operand is less than or equal to the source operand.

If we send a packet_data_len of value 0xFFFF, it will be sign-extended to 0xFFFFFFFF, treated as a negative value by the following comparison and “bypass” the length check.

Stack-based Buffer Overflow

The precedent “Integer Overflow” directly leads to a stack-based buffer overflow when the char_replace() function copies the content from the heap-buffer (at address 0x10000000) onto the CmdLine[3840] buffer using the length we have specified in the packet_header.packet_data_len field.

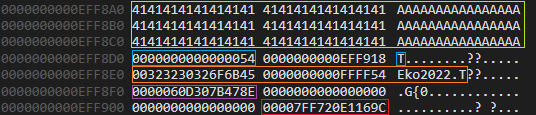

Before trashing the stack with the linear overflow we have, is always better to check what’s interesting on it. If with a debugger we check what’s left on the stack, after the CmdLine[3840] buffer, we will discover a couple of things:

-

Green: the content of the CmdLine buffer (filled with A’s up to its limit not to trigger the stack-based buffer overflow yet).

Green: the content of the CmdLine buffer (filled with A’s up to its limit not to trigger the stack-based buffer overflow yet).

- Blue: the content of the packet_type local variable.

- Orange: the content of the packet_header buffer we’ve previously sent to the server.

- Violet: the stack canary/cookie. Remember, the binary was compiled with the /GS flag and before data_processing()’s epilogue we can see a call to __security_check_cookie() function.

- Red: the saved return pointer for the main() function.

Mitigations

Simply overwriting the saved return pointer is not a viable option as we’ll also end up overwriting the stack canary, causing the OS to kill the entire process.

Unfortunately, we do not have an information leak either as the send() function, responsible for echoing back the content of the CmdLine buffer, is not using the data_lenght value we control in the packet’s header but the actual size of packet_data we’ve sent.

We should definitely come up with something different.

Type Confusion

As mentioned before, one of the interesting pieces of data left on the stack, and sitting below our buffer, is the content of the packet_type local variable. This value is later used for the type-check comparisons:

As we can overwrite its value (using the linear stack-based buffer overflow previously discovered), we can cause a “type confusion” and end up in the X case.

Code Execution

If we successfully trigger the type confusion, the program will directly jump into the heap-buffer containing our packet_data and the data written during the heap-buffer “initialization” (0x5050505050505050 and 0xCF58585858585858).

These initialization bytes are not random, in fact, they are disassembled as:

Without any further modification the software crash with an Access Violation error on the iretd instruction.

Note: the execution flow always jumps in the heap-buffer after the bytes we control. Cause of that, we cannot “bypass” nor overwrite the iretd instruction.

If we really want to crack this challenge we should dive into the iretd instruction.

iretd

Looking at the x86 Instruction Set Reference:

IRETD – interrupt return double (32-bit operand size):

Returns program control from an exception or interrupt handler to a program that was interrupted by an exception, an external interrupt, or a software-generated interrupt. In Real-Address Mode, the IRET instruction performs a far return to the interrupted program. During this operation, the processor pops the return instruction pointer, return code segment selector, and EFLAGS image from the stack to the EIP, CS, and EFLAGS registers, respectively, and then resumes execution of the interrupted program or procedure.

Since we control the stack, we’re only left with the task of crafting it in a way that would allow us to gain code execution.

IRETD expects the following values on the stack:

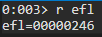

We can easily point EIP and ESP to our heap-buffer we control, while I’ve taken the EFLAGS value from WinDbg.

- EIP: 0x10000014 start of our heap-buffer plus an offset; used to directly land at the beginning of our shellcode.

- ESP: 0x10000800 a “safe” place in the “middle” of our heap-buffer. Not at the beginning of our heap-buffer, as the shellcode will sit there, and not at the end to avoid stack’s consumption messing up outside the boundaries of the heap-buffer region, triggering access violation errors.

-

EFLAGS: 0x246

- SS and CS on the other hand, were more difficult…

Global Descriptor Table

SS and CS are used to index the Global Descriptor Table (GDT) which has descriptors for:

- 0x00: Null descriptor

- 0x10: Kernel code segment

- 0x18: Kernel data segment

- 0x20: User code segment

- 0x28: User data segment

We can explore them in a kernel-mode debugger, such as WinDbg, with the following command:

The first 24 bytes are “reserved” for kernel. For user mode, we want to use selectors 0x20 and 0x28.

However, it’s not quite that straightforward. Because the selectors are all 16 bytes in size, the two least significant bits of the selector will always be zero. Intel uses these two bits to represent the Requested Privilege Level (RPL). These are zero when operating in ring-0 (kernel), but as we want to move to ring-3 (user mode) we must set them to “3”.

This means that our code segment selector will be (0x20 | 0x3 = 0x23), and our data segment selector will be (0x28 | 0x3 = 0x2B).

Now, if for the code selector we don’t have any problem, the data selector on the other hand falls into to the “bad bytes” replaced by the char_replace() function.

For the code selector, we just need to find a value whose type is Data, RW. I’ve looped through all the selectors and ended up with the value 0x53:

- CS: 0x23 code segment selector

- SS: 0x53 stack segment selector

Using the above settings will pivot the code execution flow up to the beginning of our shellcode but in 32-bit mode. Unfortunately, since the stack base and limit are completely messed up, as soon as we try to use the stack (e.g., PUSH EAX) the program will crash.

To properly execute our shellcode, I’ve introduced the following “prologue” at the beginning of our shellcode:

This “prologue” will jump some bytes further in our prologue and it also has the nice property of allowing us to specify 0x33 as the new code segment, bringing us back into 64-bit mode.

Note: if you’re wondering why I’m allowed to use the 0x33 value, note that, it is a “bad byte” only on the stack but we’re now in the heap where it can lie unaffected.

Since x64-bit doesn’t need a valid stack segment selector (it’s not used), we can finally restore the stack pointer to a meaningful value. Luckily enough, the RCX register still holds a reference to the original stack, before it was “polluted” by the IRETD instruction. We can just transfer it back into RSP with:

With everything restored we can execute the shellcode and finally pop calc!

Video PoC and Exploit

The complete (and commented) exploit code, IDA’s DB and target binary are available on my GitHub.

<iframe src="https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/UQ-IRB0fUMU" width="560" height="315" frameborder="0"> Exploit Source Code

Resources & References

- https://mudongliang.github.io/x86/html/file_module_x86_id_145.html

- http://jamesmolloy.co.uk/tutorial_html/10.-User%20Mode.html

- https://www.malwaretech.com/2014/02/the-0x33-segment-selector-heavens-gate.html

- https://nixhacker.com/segmentation-in-intel-64-bit/

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/14812160/near-and-far-jmps

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/39310831/implement-x86-to-x64-assembly-code-switch