| 关联规则 | 关联知识 | 关联工具 | 关联文档 | 关联抓包 |

| 参考1(官网) | |

| 参考2 | |

| 参考3 |

In late August of 2018, a Windows local privilege escalation zero-day exploit was released by a researcher who goes with the Internet moniker SandboxEscaper. In less than two weeks from the time the zero-day was published on Internet, the exploit was picked up by malware authors. as stated by ESET, and caused a bit of chaos in the InfoSec community. This incident also raised FortiGuard Labs’ awareness. [出自:jiwo.org]

FortiGuard Labs believes that understanding how this attack works will significantly help other researchers find vulnerabilities similar to the bug that SandboxEscaper found in the Windows Task Scheduler. In this blog post, we will discuss our approach to finding privilege escalation by abusing a symbolic link on an RPC server.

It turns out that Windows Task Scheduler had flaws in one of its Remote Procedure Calls (RPC) Application Programming Interfaces (API) exposed via an RPC server. The fact is, most RPC servers are hosted by system processes running with local system privilege, and allow RPC clients with lower privilege to interact with them. As with other software, these RPC servers might be susceptible to software issues like denial of service, memory corruption, and logical errors, etc. In other words, an attacker could leverage any vulnerabilities that might exist in an RPC servers.

One of the reasons this zero-day exploit became so popular so quickly is because the underlying vulnerability is so simple to exploit. It is caused by a program logic error which is relatively easy to spot when the correct tools and techniques are used. This particular kind of privilege escalation vulnerability is typically exploited using a bogus symbolic link to escalate files or folders, that in turn could result in privilege elevation for a normal user. For those interested, there are plenty of resources about symbolic link attacks that have been shared by James Forshaw from Google Project Zero.

RPC Server Runtime and Static Analysis Prerequisites

When conducting a new research topic, it is always a good idea to look around to see if there is any available open source tool you can leverage before writing your own tool from scratch. Fortunately, Microsoft RPC is a well-known protocol and has been well reverse-engineered by researchers over the past couple of decades. As a result, researchers have open-sourced a tool named RpcView, which is a very handy tool for identifying RPC services running on the Windows Operating System. This is definitely one of my favourite RPC tools, with many useful features such as searching the RPC interface Universal Unique Identifier (UUID), RPC interface names, etc.

However, it does not serve our purpose here to decompile and export all the RPC information into a text file. Fortunately, upon reading the source code we found that the authors have included the functionality we need, but it is not enabled by default and can only be triggered in debug mode with a specific command line parameter. Because of this limitation, we enabled and adapted the existing DecompileAllInterfaces function into an RpcView GUI. If you are interested in using this feature, our custom RpcView tool is available on our Github repository. We can now discuss the benefit of the “Decompile All Interfaces” feature in the next section.

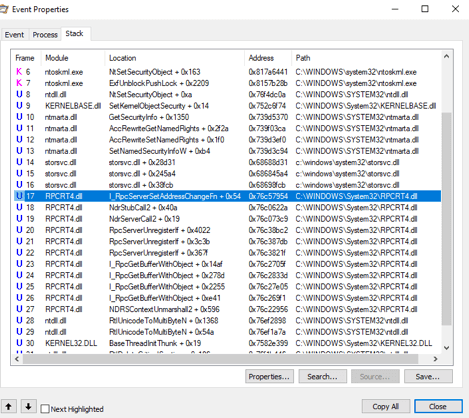

Figure 1: RpcView Decompile All Interfaces feature

Figure 1: RpcView Decompile All Interfaces feature

When analysing the behaviours of an RPC server, we always call the APIs exposed via the RPC interface. Such interaction with an RPC server of interest can be achieved by sending an RPC request via the RPC Client to the server and then observing its behaviours using the Process Monitor tool in SysInternals. In my opinion, the most convenient way to do this is by scripting rather than writing a C/C++ RPC client that requires program compilation, which is time consuming.

Instead, we are going to use PythonForWindows. It provides abstractions around some of the Windows features in a pythonic way, which relies heavily on Python’s ctypes. It also consists of an RPC library which provides some convenient wrapper functions that save us time when writing the RPC client. For example, a typical RPC client binary needs to define the interface definition language, and you need to manually implement the binding operation, which usually involves some C++ codes. See Listing 1 and Listing 2, below, that illustrate the difference between scripting and programming the RPC client with minimal error handling code.

import sys import ctypes import windows.rpc import windows.generated_def as gdef from windows.rpc import ndr StorSvc_UUID = r"BE7F785E-0E3A-4AB7-91DE-7E46E443BE29" class SvcSetStorageSettingsParameters(ndr.NdrParameters): MEMBERS = [ndr.NdrShort, ndr.NdrLong, ndr.NdrShort, ndr.NdrLong] def SvcSetStorageSettings(): print "[+] Connecting...." client = windows.rpc.find_alpc_endpoint_and_connect(StorSvc_UUID, (0,0)) print "[+] Binding...." iid = client.bind(StorSvc_UUID, (0,0)) params = SvcSetStorageSettingsParameters.pack([0, 1, 2, 0x77]) print "[+] Calling SvcSetStorageSettings" result = client.call(iid, 0xb, params) if len(str(result)) > 0: print " [*] Call executed successfully!" stream = ndr.NdrStream(result) res = ndr.NdrLong.unpack(stream) if res == 0: print " [*] Success" else: print " [*] Failed" if __name__ == "__main__": SvcSetStorageSettings()

Listing 1: SvcSetStorageSettings using PythonForWindows RPC Client

RPC_STATUS CreateBindingHandle(RPC_BINDING_HANDLE *binding_handle) { RPC_STATUS status; RPC_BINDING_HANDLE v5; RPC_SECURITY_QOS SecurityQOS = {}; RPC_WSTR StringBinding = nullptr; RPC_BINDING_HANDLE Binding; StringBinding = 0; Binding = 0; status = RpcStringBindingComposeW(L"BE7F785E-0E3A-4AB7-91DE-7E46E443BE29", L"ncalrpc", nullptr, nullptr, nullptr, &StringBinding); if (status == RPC_S_OK) { status = RpcBindingFromStringBindingW(StringBinding, &Binding); RpcStringFreeW(&StringBinding); if (!status) { SecurityQOS.Version = 1; SecurityQOS.ImpersonationType = RPC_C_IMP_LEVEL_IMPERSONATE; SecurityQOS.Capabilities = RPC_C_QOS_CAPABILITIES_DEFAULT; SecurityQOS.IdentityTracking = RPC_C_QOS_IDENTITY_STATIC; status = RpcBindingSetAuthInfoExW(Binding, 0, 6u, 0xAu, 0, 0, (RPC_SECURITY_QOS*)&SecurityQOS); if (!status) { v5 = Binding; Binding = 0; *binding_handle = v5; } } } if (Binding) RpcBindingFree(&Binding); return status; } VOID RpcSetStorageSettings() { RPC_BINDING_HANDLE handle; RPC_STATUS status = CreateBindingHandle(&handle); if (status != RPC_S_OK) { _tprintf(TEXT("[-] Error creating handle %d\n"), status); return; } RpcTryExcept { if (!SUCCEEDED(SvcSetStorageSettings(0, 1, 2, 0x77)) { _tprintf(TEXT("[-] Error calling RPC API\n")); return; } } RpcExcept(1) { RpcStringFree(&instanceid); } RpcEndExcept }

Listing 2: SvcSetStorageSettings using C++ RPC Client

After the RPC client has successfully executed the corresponding RPC API, we used the Process Monitor to monitor its activities. Process Monitor is helpful in dynamic analysis as it provides event-based API runtime information. It is worth mentioning that one of the probably lesser known features of Process Monitor is its call-stack information, as shown in Figure 2, which enables you to trace the API calls of an event.

Figure 2: Process Monitor API call-stack

Figure 2: Process Monitor API call-stack

We can use the Address and Path information to pinpoint exactly the corresponding module and function routine when doing static analysis via a disassembler like IDA Pro, for instance. This is useful because sometimes you might not be able to spot the potential symbolic link attack patterns using the Process Monitor output alone. This is why static analysis via disassembler comes into play in helping us in discovering race condition issues, which will be discussed in the second part of this blog series.

Microsoft Universal Telemetry Client (UTC) Case Study

Have you ever heard that Microsoft is collecting customer information, data, and file starting details on Windows 10 and above? Have you ever wondered how this works? If you are interested, you can read about it in this excellent article about the mechanism behind UTC.

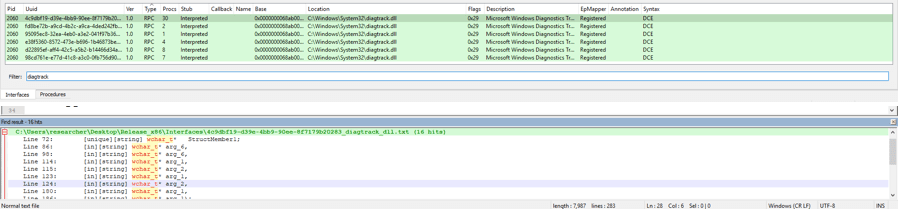

To start the next phase of our analysis, we first exported all the RPC interfaces from the RpcView GUI to text files. The resulting text files consisted of all the RPC APIs that were callable from the RPC Servers. From the output text files we then looked for the RPC APIs that accept wide string as input until we encountered one of the more interesting RPC interfaces from diagtrack.dll. Later, we confirmed that this DLL component is responsible for the implementation of UTC functionality, especially when judging from the name Microsoft Windows Diagnostic Tracking, from its description shown in the RpcView GUI.

Figure 3: RpcView reveals UTC’s DLL component, and one of its RPC interfaces accepts wide string as input

Figure 3: RpcView reveals UTC’s DLL component, and one of its RPC interfaces accepts wide string as input

Keep in mind that our goal here is to find the API that could possibly accept an input file path that could eventually lead to privilege escalation, as demonstrated by the Windows Task Scheduler bug. But that requirement alone gives us 16 possible APIs, as shown in Figure 3. Obviously, we need to filter out those APIs that are out of our interest. So we used IDA Pro and started with static analysis to find out which API we should dive into.

I normally first locate the RPC function RpcServerRegisterIf, which is typically used to register an interface specification over RPC server. The interface specification contains the definition of the RPC interface hosted by a particular RPC server. According to the MSDN document, the interface specification is located in the first parameter of the function, which is represented by the RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE data structure with the following definition:

struct _RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE { unsigned int Length; RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER InterfaceId; RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER TransferSyntax; PRPC_DISPATCH_TABLE DispatchTable; unsigned int RpcProtseqEndpointCount; PRPC_PROTSEQ_ENDPOINT RpcProtseqEndpoint; void *DefaultManagerEpv; const void *InterpreterInfo; unsigned int Flags; };

The InterpreterInfo of the interface specification is a pointer to the MIDL_SERVER_INFO data structure, which consists of a DispatchTable pointer that keeps the information of the interface APIs supported by the specific RPC interface. This is indeed the field we are looking for.

typedef struct _MIDL_SERVER_INFO_ { PMIDL_STUB_DESC pStubDesc; const SERVER_ROUTINE* DispatchTable; PFORMAT_STRING ProcString; const unsigned short* FmtStringOffset; const STUB_THUNK* ThunkTable; PRPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER pTransferSyntax; ULONG_PTR nCount; PMIDL_SYNTAX_INFO pSyntaxInfo; } MIDL_SERVER_INFO, *PMIDL_SERVER_INFO;

Figure 4 is an animation that illustrates how we typically traverse the import address table to determine the DispatchTable within IDA Pro.

Figure 4: Determining RPC exposed APIs by traversing IAT within IDA Pro

Figure 4: Determining RPC exposed APIs by traversing IAT within IDA Pro

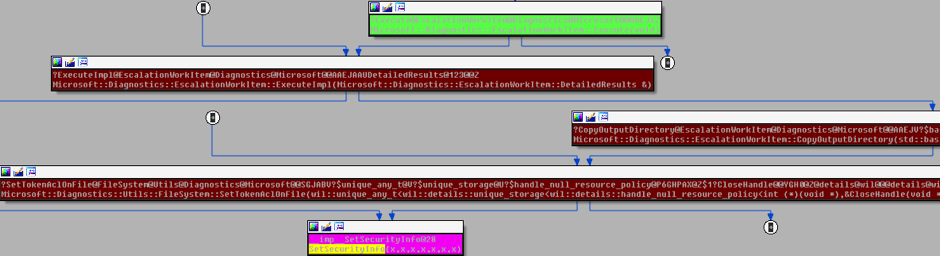

After we have determined the UTC’s interface APIs with the UtcApi prefix, as shown in Figure 4, we tried to determine if any of these interface APIs would lead to any Access Control List (ACL) APIs, such as SetNamedSecurityInfo and SetSecurityInfo. We are interested in these ACL APIs because they are used in changing the discretionary access control (DACL) security descriptor of an object, whether it’s a file, directory, or registry object. Another useful feature in IDA Pro that is probably underused is its proximity view, which shows you a call-graph of a function routine that will be displayed in a graph form. We used the proximity view to find the function routine that is being referenced or called by the ACL APIs mentioned above.

Figure 5: IDA’s Proximity view that shows the correlation between SetSecurityInfo and the function routines in diagtrack.dll

Figure 5: IDA’s Proximity view that shows the correlation between SetSecurityInfo and the function routines in diagtrack.dll

However, IDA Pro did not yield any results when we tried to look for the correlation between SetSecurityInfo and UtcApi. Digging further, we found out that the UtcApi placed the client’s RPC request into the workitem queue that will be processed by asynchronous thread. As shown in Figure 5, SetSecurityInfo will be executed when Microsoft::Diagnostic::EscalationWorkItem::Execute is triggered. Basically, this is a call-back function that is responsible for executing escalation requests kept in the work item submitted by the RPC client.

At this point, we needed to figure out how to submit an escalation request. After playing around with various applications, we came across Microsoft Feedback Hub, which is a Universal Windows Platform (UWP) application that comes by default on Windows 10. Sometimes, you might find it useful to debug a UWP application. Unfortunately, you cannot open or attach a UWP application directly under WinDbg and expect it to work magically. However, UWP application debugging can be enabled via PLMDebug tool that comes with Window Debugger included in Windows 10 SDK. You can first determine the full package family name of the Feedback Hub via the Powershell built-in cmdlet:

PS C:\Users\researcher> Get-AppxPackage | Select-String -pattern "Feedback" Microsoft.WindowsFeedbackHub_1.1809.2971.0_x86__8wekyb3d8bbwe PS C:\Users\researcher> cd "c:\Program Files\Windows Kits\10\Debuggers\x86" PS C:\Program Files\Windows Kits\10\Debuggers\x86> PS C:\Program Files\Windows Kits\10\Debuggers\x86> .\plmdebug.exe /query Microsoft.WindowsFeedbackHub_1.1809.2971.0_x86__8wekyb3d8bbwe Package full name is Microsoft.WindowsFeedbackHub_1.1809.2971.0_x86__8wekyb3d8bbwe. Package state: Unknown SUCCEEDED PS C:\Program Files\Windows Kits\10\Debuggers\x86>

After we obtained full package name, we enables UWP debugging for the Feedback Hub using PLMDebug again:

c:\Program Files\Windows Kits\10\Debuggers\x86>plmdebug.exe /enabledebug Microsoft.WindowsFeedbackHub_1.1809.2971.0_x86__8wekyb3d8bbwe "c:\program files\windows kits\10\Debuggers\x86\windbg.exe" Package full name is Microsoft.WindowsFeedbackHub_1.1809.2971.0_x86__8wekyb3d8bbwe. Enable debug mode SUCCEEDED

The next time you launch the Feedback Hub, the application will be executed and attached to WinDbg automatically.

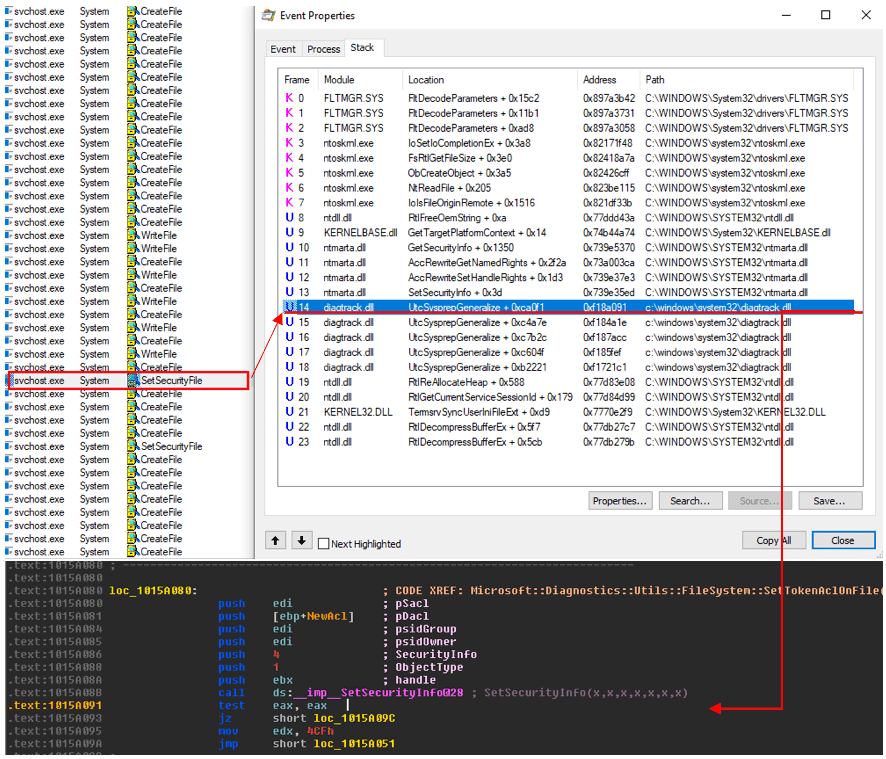

Figure 6: Determining the offset of the API call from Process Monitor Event Properties

Figure 6: Determining the offset of the API call from Process Monitor Event Properties

After we’d launched the Feedback Hub, we followed the on-screen instructions from the application and we started seeing activities in the Process Monitor. This is a good sign, as it implies that we are on track. When we then looked into the call-stack of the highlighted SetSecurityFile event, we found the return address of the ACL API SetSecurityInfo at offset 0x15A091 (the base address of diagtrack.dll can be found in Process tab of Event Properties). As you can see, this offset falls within the routine Microsoft::Diagnostics::Utils::FileSystem::SetTokenAclOnFile, as shown under the disassembler in Figure 6, and that also appears in the proximity view demonstrated in Figure 5. This proves that we can utilize the Feedback Hub to reach our desired code path.

In addition to that, the Process Monitor output also told us that this event attempts to set the DACL of the file object, but determining how the file object was derived by doing code static analysis might be time-consuming. Fortunately, we can attach a local debugger to the svchost.exe program that was hosting the UTC service that was given administrative rights because the process is not protected by the Protected Process Light (PPL) mechanism. This gives us the flexibility to dynamically debug the UTC service to understand how the file path was retrieved.

Under the hood, all feedback details and attachments will be kept in a temporary folder with the format %DOCUMENTS%\FeedbackHub\<guid>\diagtracktempdir<random_decimals> after you have submitted it via the Feedback Hub. The random decimal number appended to diagtracktempdir is generated via the BCryptGenRandom API, which means that the generated number is literary unpredictable. But one of the most important criteria in a symbolic link attack is to be able to predict the file or folder name, so the random diagtracktempdir name increases the difficultly of exploiting the symbolic link vulnerability. Therefore, we dove into other routines to find other potential issues.

While we were trying to understand how the diagtracktempdir security descriptor is set, we realized that the folder will be created with the explicit security descriptor string of O:BAD:P(A;OICI;GA;;;BA)(A;OICI;GA;;;SY), which implies that the DACL of the object will be granted for Administrator and local system user access only. However, the explicit security descriptor will be ignored if the following registry key is set accordingly:

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Diagnostics\DiagTaskTestHooks\Volatile

“NoForceCopyOutputDirAcl” = 1

In a nutshell, diagtracktempdir will be enforced to use an explicit security descriptor when the above registry key is not present, otherwise the default DACL will be applied to the folder that could potentially raise some security issues, as there is no impersonation token being used during folder creation. Nevertheless, you can bypass the explicit security descriptor to this folder if you have an arbitrary registry write vulnerability. But this is not what we are pursuing, so our best bet is to look into the Process Monitor again:

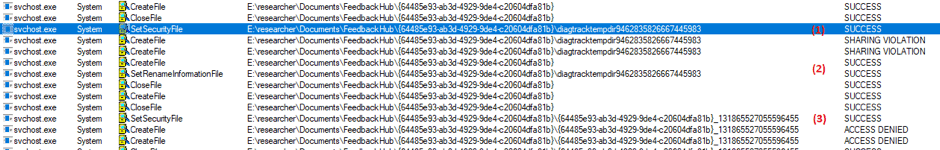

Figure 7: Setting DACLs and renaming folder diagtracktempdir

Figure 7: Setting DACLs and renaming folder diagtracktempdir

Basically we can summarize the operations labelled in Figure 7 as follows:

1. Grant access to the current logged-in user on diagtracktempdir under local system privilege

2. Rename diagtracktempdir to the GUI-styled folder under impersonation

3. Revoke access of the current logged-in user on diagtracktempdir under impersonation

The following code snippet corresponds to the operations shown in Figure 7:

bQueryTokenSuccessful = UMgrQueryUserToken(hContext, v81, &hToken); if ( hToken && hToken != -1 ) { // This will GRANT access of the current logged in user to the directory in the specified handle bResultCopyDir = Microsoft::Diagnostics::Utils::FileSystem::SetTokenAclOnFile(&hToken, hDir, Sid, GRANT_ACCESS) if ( !ImpersonateLoggedOnUser(hToken) ) { bResultCopyDir = 0x80070542; } } // Rename diagtracktempdir to GUID-styled folder name bResultCopyDir = Microsoft::Diagnostics::Utils::FileSystem::MoveFileByHandle(SecurityDescriptor, v65, Length); if ( bResultCopyDir >= 0 ) { boolRenamedSuccessful = 1; // This will REVOKE access of the current logged in user to the directory in the specified handle bSetAclSucessful = Microsoft::Diagnostics::Utils::FileSystem::SetTokenAclOnFile(&hToken, hDir, Sid, REVOKE_ACCESS) if (bSetAclSucessful) { // Cleanup and RevertToSelf return; } } else { lambda_efc665df8d0c0615e3786b44aaeabc48_::operator_RevertToSelf(&hTokenUser); // Delete diagtracktempdir folder and its contents lambda_8963aeee26028500c2a1af61363095b9_::operator_RecursiveDelete(&v83); }

Listing 3: Grant and then revoke access on diagtracktempdir

From Listing 3, we can tell when the file rename operation failed. If the bResultCopyDir has a value of less than 0, it will proceed to the RecursiveDelete function call. It is also worth noting that it calls the RevertToSelf function to terminate the impersonation before the RecursiveDelete function is called, which means the target directory and its contents can be deleted under local system privilege, that would allow us to achieve arbitrary files deletion if we managed to use a symbolic link to redirect the diagtracktempdir to an arbitrary folder. Fortunately, Microsoft has mitigated the potential reparse point deletion issues. This RecursiveDelete function has explicitly skipped any directory or folder that has the FILE_ATTRIBUTE_REPARSE_POINT flag set, which is typically set for a junction folder. So we can confirm that this recursive deletion routine does not pose any security risks.

Since we are not able to demonstrate arbitrary file deletion, we decided to show off how to write arbitrary files to diagtracktempdir directory. Looking into the code, we realized that UTC service does not revoke the security descriptor of the diagtracktempdir for a currently logged in user after the recursive deletion routine has completed. This is intentional, because you do not need to impose a new DACL to a folder that is going to be removed, which is redundant work. But this has also opened up a potential race condition opportunity for the attacker to prevent the deletion of the escalated diagtracktempdir by creating a file with an exclusive file handle in the same directory. The RecursiveDelete function encounters a sharing violation when attempting to open and delete the file with an exclusive file handle and then exit the operation gracefully. After all, the attacker could drop and execute files in the escalated diagtracktetempdir in a restricted directory, for example C:\WINDOWS\System32.

So the next question is, how did we make the file rename operation fail? Looking into the underlying implementation of Microsoft::Diagnostics::Utils::FileSystem::MoveFileByHandle, we see that it is essentially a wrapper function calling the SetFileInformationByHandle API. It appears that the underlying kernel functions derived from this API will always obtain the file handle of the parent directory with write access. For example, if the handle is currently referenced to c:\blah\abc it will attempt to get the file handle with write access of c:\blah. However, if we specify a directory in which the current logged in user has no write access to, Microsoft::Diagnostics::Utils::FileSystem::MoveFileByHandle could fail to execute properly. The following file paths are good candidates, as they are known to be restricted folders that disallow folder creation for a normal user account:

· C:\WINDOWS\System32

· C:\WINDOWS\tasks

There should not be any problem of winning this race condition as some of the escalation requests involve writing a bunch of log files to our controlled diagtracktempdir and they will take some time to be deleted. So we should be able to win the race most of the time in a modern system with multiple cores if we have successfully created an exclusive file handle in our target directory.

Next, we need to find ways to trigger the code path programmatically using the correct parameters required by UtcApi. Being able to debug and set the breakpoint on the RPC function, the NdrClientCall within the Feedback Hub really makes our life easier. The debugger reveals the scenario ID as well as the escalation path that we should send to UtcApi. In this case, we are going to use the scenario ID {1881A45E-01FD-4452-ACE4-4A23666E66E3} as it seems to consistently show up whenever the UtcApi_EscalateScenarioAsync routine is triggered, and it has led to our desired code path on the RPC Server. Take note that the escalation path has also allowed us to control where diagtracktempdir will be created.

Breakpoint 0 hit eax=0c2fe7b8 ebx=032ae620 ecx=0e8be030 edx=00000277 esi=0c2fe780 edi=0c2fe744 eip=66887154 esp=0c2fe728 ebp=0c2fe768 iopl=0 nv up ei pl nz na po nc cs=001b ss=0023 ds=0023 es=0023 fs=003b gs=0000 efl=00000202 Helper+0x37154: 66887154 ff15a8f08866 call dword ptr [Helper!DllGetActivationFactory+0x6d31 (6688f0a8)] ds:0023:6688f0a8={RPCRT4!NdrClientCall4 (76a74940)} 0:027> dds esp l9 0c2fe728 66892398 Helper!DllGetActivationFactory+0xa021 0c2fe72c 66891dca Helper!DllGetActivationFactory+0x9a53 0c2fe730 0e8be030 0c2fe734 1881a45e // Scenario ID 0c2fe738 445201fd 0c2fe73c 234ae4ac 0c2fe740 e3666e66 0c2fe744 00000000 0c2fe748 032ae620 // Escalation path 0:027> du 032ae620 032ae620 "E:\researcher\Documents\Feedback" 032ae660 "Hub\{e04b7a09-02bd-42e8-a5a8-666" 032ae6a0 "b5102f5de}\{e04b7a09-02bd-42e8-a" 032ae6e0 "5a8-666b5102f5de}"

As a result, the prototype of UtcApi_EscalateScenarioAsync looks like the following:

long UtcApi_EscalateScenarioAsync ( [in] GUID SecnarioID, [in] int16 unknown, [in] wchar_t* wszEscalationPath [in] long unknown2, [in] long unknown3, [in] long num_of_keyval_pairs, [in] wchar_t **keys, [in] wchar_t **values)

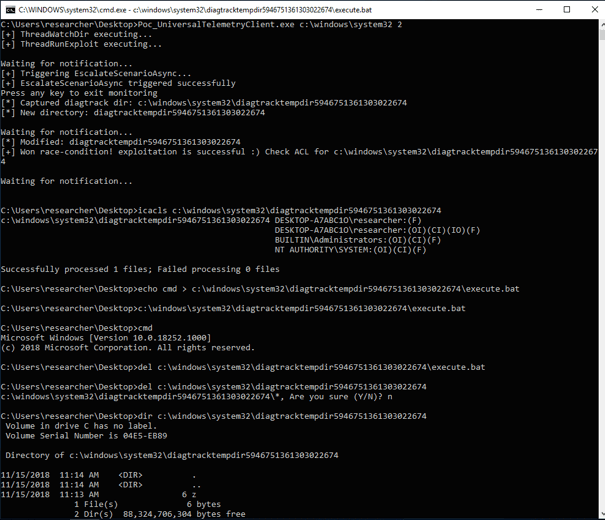

Putting all of this together, our proof of concept (PoC) flows like this:

- Create an infinite thread that will monitor our target directory, eg: C:\WINDOWS\SYSTEM32, in order to capture the folder name of diagtracktempdir

- Create another infinite thread that will create an exclusive file handle into C:\WINDOWS\SYSTEM32\diagtracktempdir{random_decimal}\z

- Call UtcApi_EscalateScenarioAsync(1881A45E-01FD-4452-ACE4-4A23666E66E3) to trigger Microsoft::Diagnostic::EscalationWorkItem::Execute

- C:\WINDOWS\SYSTEM32\diagtracktempdir{random_decimal}\z will have been created successfully if we have won the race

- After that, the attacker can write and execute arbitrary files to the escalated folder C:\WINDOWS\SYSTEM32\diagtracktempdir{random_decimal} to bypass legitimate programs that have always assumed that %SYSTEM32% directory contains only legitimate OS files

The result of our PoC demonstrates the potential ways to create arbitrary files and folders in a static folder under a restricted directory by leveraging the UTC service.

Figure 8: PoC allowed creating arbitrary files in diagtracktempdir

Figure 8: PoC allowed creating arbitrary files in diagtracktempdir

To reiterate, this PoC does not pose a security risk to Windows OS without also being able to control or rename the folder diagtracktempdir, as stated by the MSRC. However, it is common to see malware authors utilizing different techniques such as User Account Control (UAC) bypass in order to write files to a Windows system folder with the intention of bypassing a delicate heuristic detector. In fact, while exploring the potential file paths to be used in the PoC, we found that C:\WINDOWS\SYSTEM32\Tasks contains write and execute permissions for normal user accounts. but without read permission—which is why this folder is also one of the notorious target paths for malware authors to store malicious files.

Conclusion

In this first part of the blog series, we have shown you our approach to finding a potential security risk in a Windows RPC Server using different available tools and online resources. We also demonstrated some of the fundamental knowledge you need to reverse-engineer an RPC Server. We strongly believe there are still other potential security risks in the RPC Server. As a result, we are determined to harden Windows RPC Servers further. In the second part of this blog series, we will continue our investigation and improve our methodology that will lead us to uncover other RPC Server vulnerabilities.